Understanding Heatwaves: Beyond Extreme Temperatures

Published: January 29, 2026

Geneva

..

When temperatures soar, the term “heatwave” is often used loosely or even inaccurately, and the scientific definition is admittedly not very palatable unless one is well-versed in the intricacies of weather phenomena.

A heatwave is a weather phenomenon defined by the ‘local cumulative excess heat over a sequence of unusually hot days and nights.’ To understand what this means in practice, consider the relationship between heat and a system’s capacity to store it. Whether we are looking at the environment or city infrastructure, these systems possess heat inertia – which means they absorb heat slowly but also require time to release it.

To remain functional, these systems need a “reset” period. If a very hot day is followed by a sufficiently cool night, the physical environment can discharge the heat absorbed, resetting temperatures. However, if a hot day is followed by a warm night, the system – whether the environment or city – cannot fully shed that energy. The heat begins to accumulate, building day after day. This failure to recover is the defining characteristic of a heatwave.

The difference between hot days and heatwaves

While climate monitoring often focuses on maximum daily temperatures, a sequence of “hot days” does not automatically constitute a heatwave.

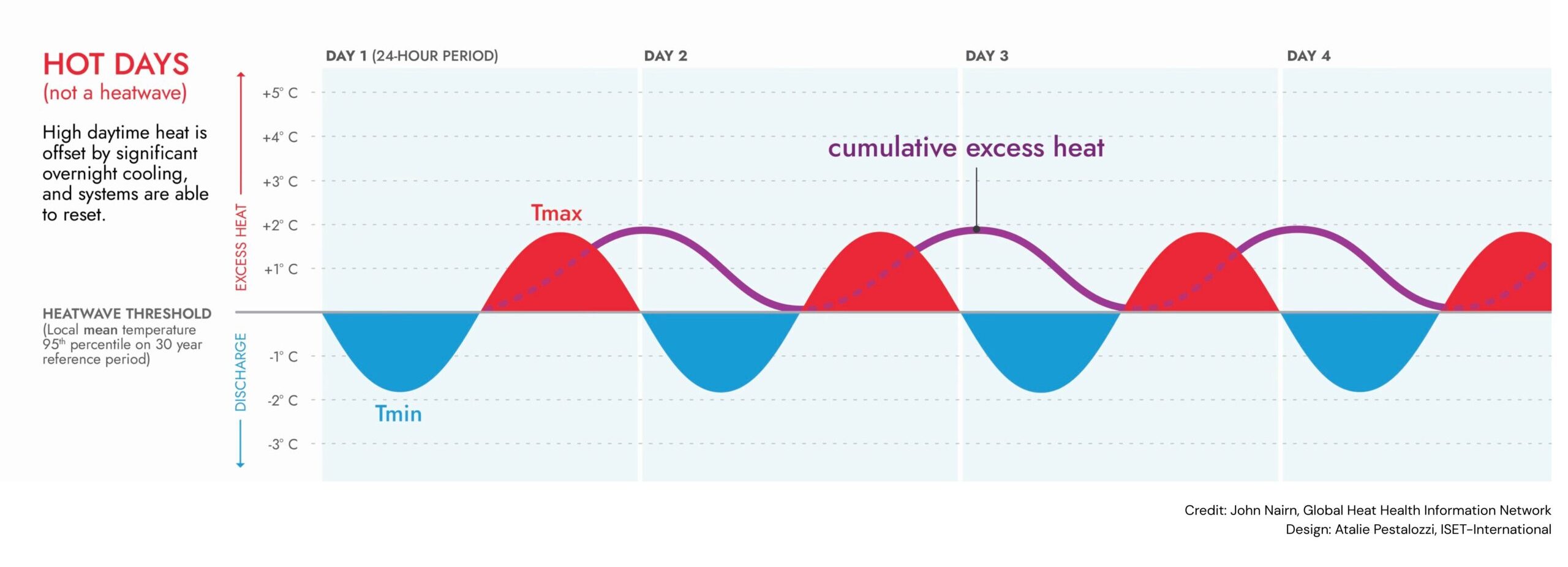

Figure 1.

Temperatures can soar during the day, but if they drop significantly at night, the “excess heat” gained during the sunlight hours is fully discharged. In this scenario, while the daytime conditions might be uncomfortable, or dangerous for vulnerable populations, the lack of cumulative heat means the event does not intensify into a heatwave.

Crucially, what constitutes a heatwave is also relative to the local environment. A “hot” night in London or Helsinki might well be considered a “cool” night in Bangkok or Riyadh. Therefore, heatwaves are defined locally, often using a mean temperature of 95th percentile threshold based on 30-years of local climate data. This means we compare today’s heat against what is “normal” for that specific climate and the adaptive capacity of its inhabitants and infrastructure.

Understanding and monitoring extreme thermal conditions – shaped by a combination of temperature, humidity, sunshine, and wind speed – is also essential to help protect human life.

In many tropical regions, people experience ongoing heat and humidity, which creates a constant level of thermoregulation (thermal) stress. Noteworthy and important, chronic heat is not necessarily coincident with heatwaves, with relatively few heatwave definitions focused on heat intensity – even though intensity is one of the most important factors for understanding health and environmental impacts. Heatwaves typically develop over large continental areas and are often characterized by very hot, relatively dry conditions that can escalate over time. Using a heatwave definition based on intensity, with clear severity categories, can support more effective impact‑based services across sectors such as health, energy, and agriculture.

Low-intensity heatwaves

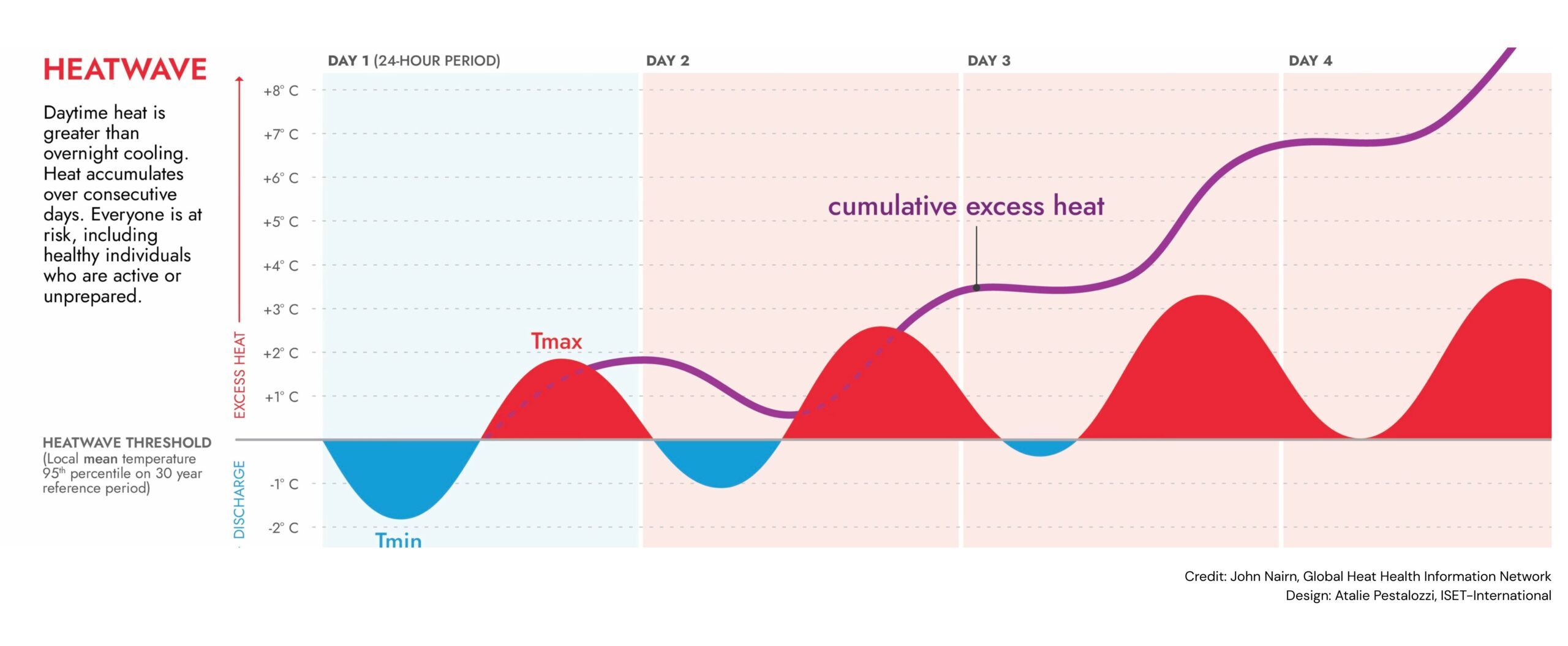

When nighttime temperatures begin to rise, the cooling window narrows. As illustrated in Figure 2, the heat discharge at night becomes smaller than the heat gained during the day. This creates a “staircase” effect where the total heat load on the community increases over time.

Figure 2.

As daytime and overnight temperatures increase, the excess heat discharge (blue) is smaller than the cumulative excess heat (red) during the day. The cumulative excess heat (purple) over the sequence of days builds as the minimum temperature rises through the local reference temperature threshold.

Most heatwaves are of this low-intensity variety. Many would consider this type of heat event as normal summer weather, and it is likely that many people will be able to reduce their exposure to this level of heat. However, it is a common misconception that only the “frail” or “elderly” vulnerable populations are at risk. Vulnerable populations – whether young or old- will benefit from targeted Heat Action Plan (HAP) initiatives to support informed decisions or health interventions to reduce their cumulative heat exposure, and/or gain cooling relief. However, anybody can experience heat impacts during a low-intensity heatwave if they are caught unprepared. For example, a healthy individual going for a run or working outdoors may suffer significant thermal stress because their body, like the infrastructure around them, is struggling to shed heat in an unusually hot environment.

High-intensity and extreme heat

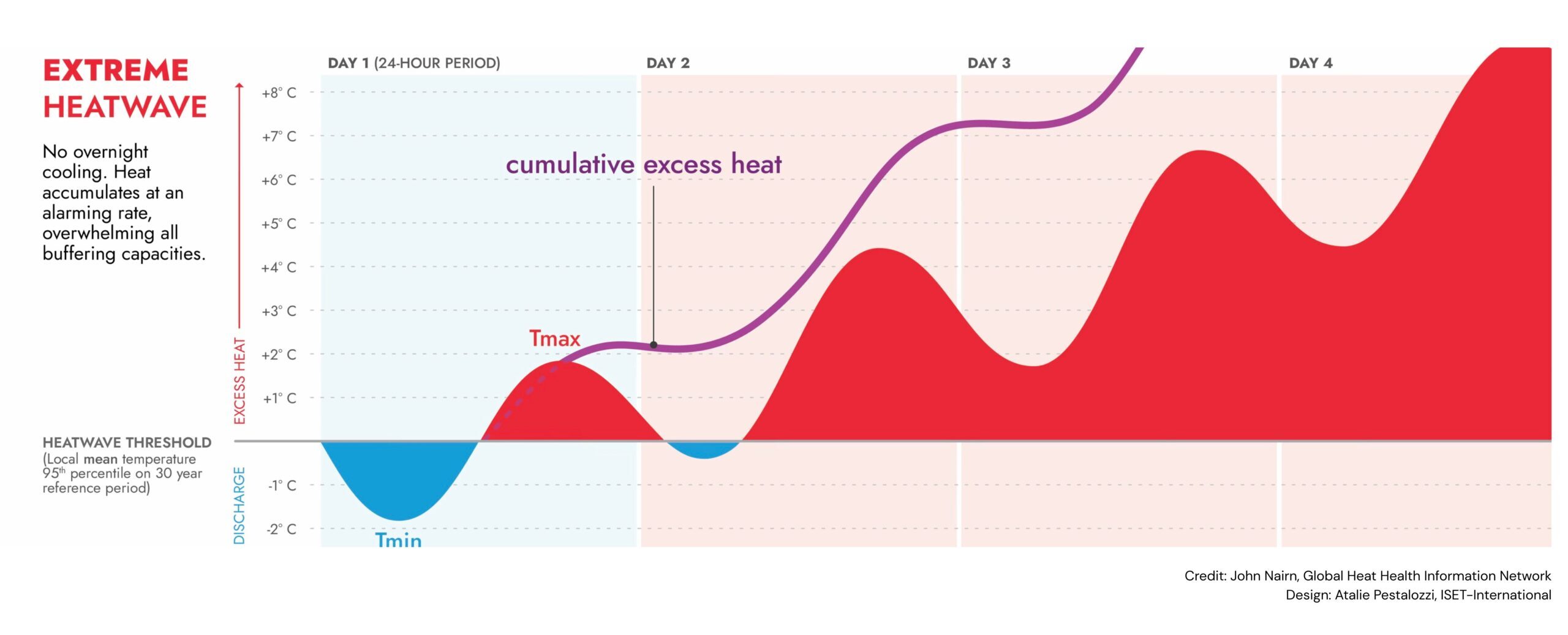

When the gap between daytime peaks and nighttime lows continues to shrink, the heatwave enters a high-intensity phase. In Figure 3, the daily temperature cycle may stay entirely above the local threshold. There is no relief; the environment is in a constant state of heat gain. As less frequent, more intense or severe heatwaves develop, a much larger number of people will benefit from public early warnings and vigorous HAP interventions. Without enhanced HAP interventions, exposure during much rarer, higher intensity extreme heatwaves become dangerous not only to those already vulnerable but the whole population, as transport and critical infrastructure systems (such as energy) lose the ability to reset and falter, and the risk of other hazards, like wildfires, rapidly escalate with increasing frequency.

Figure 3.

As the daily temperature cycle exceeds the heatwave threshold altogether, cumulative excess heat rises at an alarming rate, with little or no relief from excess heat overnight. Rising minimum temperatures produce an extreme cumulative excess heat response.

The recovery lag: why risk remains after peak heat

It is vital to recognize that the risk does not disappear the moment temperatures start to drop. Because of heat inertia, it can take several days for buildings, infrastructure, and human bodies to fully “reset” their temperatures once a heatwave has shifted to below threshold temperatures. This is why mortality and morbidity often remain elevated for days after the momentary peak temperatures.

Effective Heat Early Warning Systems must remain active and public health messaging must continue even as the weather cools, ensuring the people understand that their systems are still in a state of recovery, and know what to do to protect their health.

Distinguishing between hot days and true heatwaves is not a semantic exercise: connecting heatwave intensity with the experience of impacts is fundamental to community confidence in understanding the heatwave hazard and the triggering of timely action.

Summary:

- Hot Days (not a heatwave): When high daytime heat is offset by significant overnight cooling, and systems are able to reset.

- Heatwave: Daytime heat is greater than overnight cooling. Heat accumulates over consecutive days and nights. Everyone is at risk, including healthy individuals who are active or unprepared. Highly vulnerable people benefit from targeted support.

- Extreme heatwave: No overnight cooling. Heat accumulates at an alarming rate, overwhelming all normal heat storage capacities.

- Recovery Phase: Risk remains elevated after temperatures drop, as systems require time to discharge the heat load.

Acknowledgements:

Graphics by Atalie Pestalozzi, ISET-International.